Understanding Glioblastoma

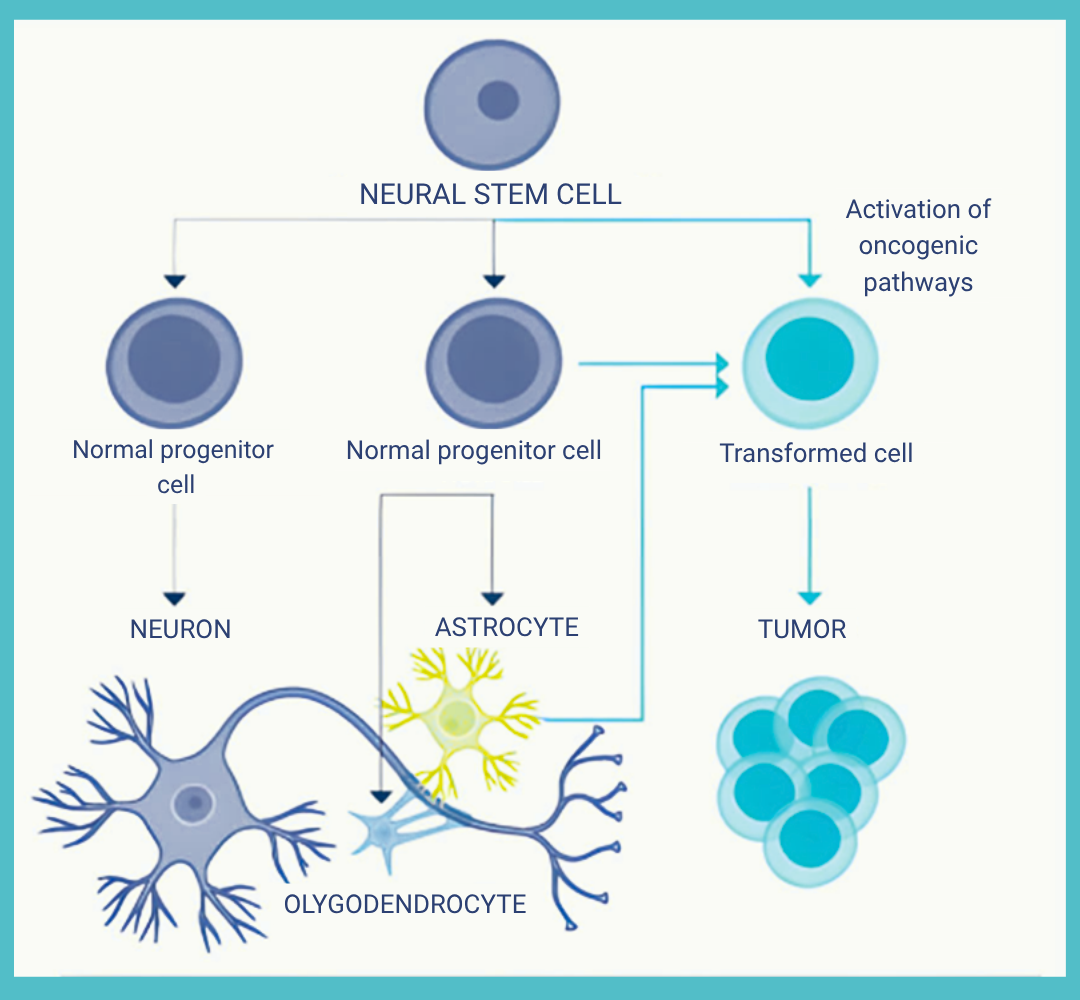

Glioblastoma, or GBM, is a particularly aggressive form of cancer that develops in the brain or spinal cord. It is the most common and most aggressive primary brain tumor in adults. Characterized by rapid growth and a high capacity to infiltrate surrounding brain tissue, GBM is classified among the most malignant tumors. It originates from astrocytes — star-shaped glial cells that support brain function, including the regulation of neural connections.

Source : Des Étoiles dans la Mer. (2021.). Comprendre mon glioblastome

One of the defining features of GBM is its pronounced heterogeneity: a single tumor can contain multiple types of cells, making it especially complex and difficult to treat.

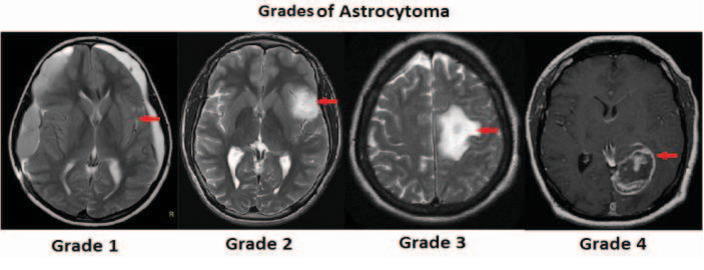

Gliomas, a category of brain tumors, are typically classified into two main groups:

- Low-grade gliomas (Grades I and II), which progress slowly

- High-grade gliomas (Grades III and IV), which are malignant

Glioblastomas are Grade IV gliomas — the highest grade — indicating an extremely aggressive form of cancer.

Source: Priya. (n.d.). Brain tumor types and grades classification based on image processing and machine learning [Figure]. Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Brain-tumor-types-and-grades-classification-based-Priya/78c487a74993a0ce3fca3e1e15610fc44594f4e0/figure/1

Although rare in the general population (accounting for approximately 1.4% of all cancers in France1) with an incidence of about 5 cases per 100,000 people per year, GBM represents a major challenge in medical research and neuro-oncology. Over the past three decades, survival rates for patients diagnosed with GBM have only modestly improved2, despite advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. This highlights the urgent need for the development of more effective therapeutic approaches.

Source: Passeport Santé. (n.d.). Glioblastome.

A Rare but Devastating Disease

Each year, around 3,500 people in France are diagnosed with glioblastoma3;4. In 2018, there were exactly 3,481 cases, with a clear male predominance (about 1.5 times more frequent than in females): 2,003 men versus 1,478 women4;5;6. The peak incidence occurs around age 65, although this tumor can also affect young adults7;8. The average age at diagnosis is 58, and incidence increases significantly with age.

Demographic projections indicate a 238% rise in the population over 65 by 2050. Since half of glioblastoma cases already affect this age group9, managing GBM in the elderly will become a major public health issue in the coming decades.

Symptoms and Risk Factors

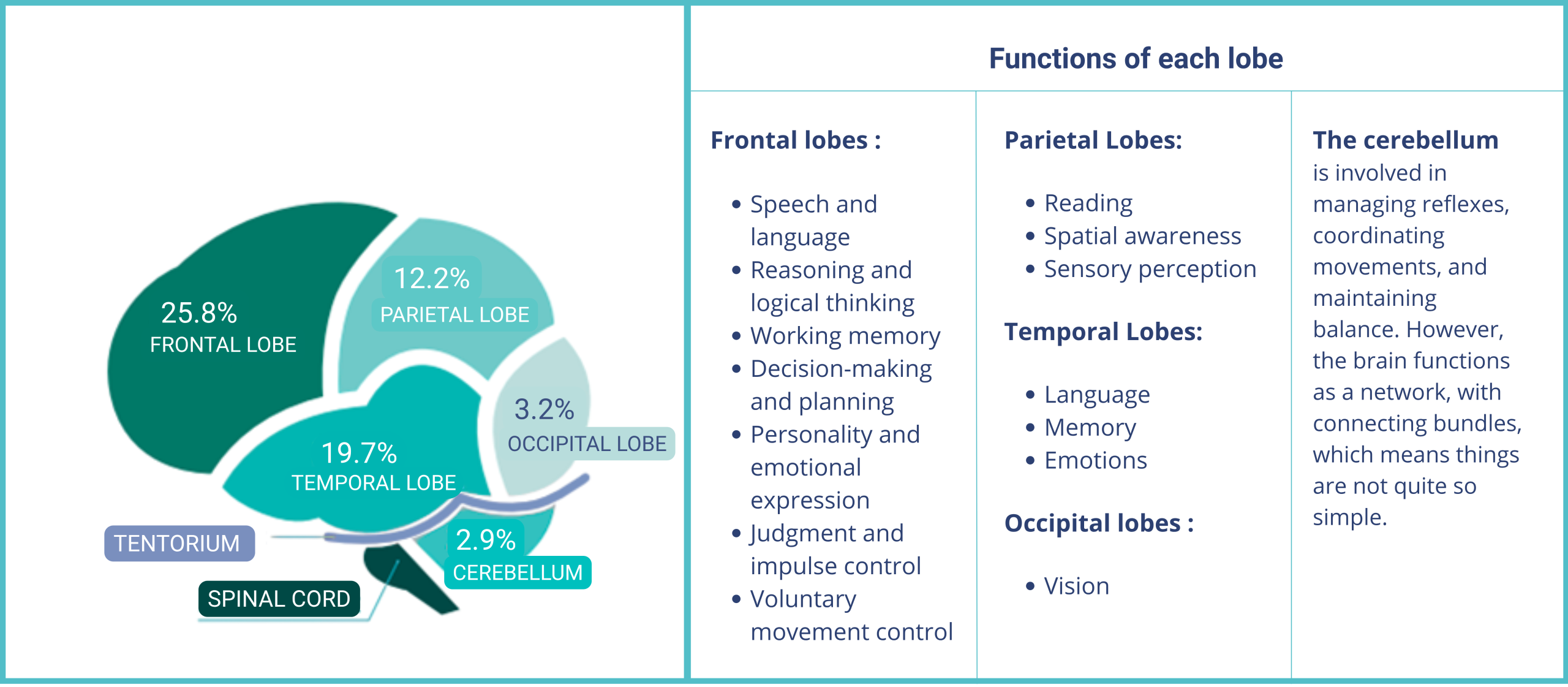

Symptoms vary depending on the tumor’s location in the brain, but the most common signs include:

- Persistent headaches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Vision and/or speech disturbances

- Seizures

- Motor or sensory deficits

These non-specific symptoms should raise concern, especially if they worsen quickly. However, only a thorough medical evaluation can confirm the diagnosis3;7;10.

The exact risk factors remain unclear, although genetic predispositions (such as Lynch syndrome or Li-Fraumeni syndrome), and exposure to certain chemicals or ionizing radiation, are recognized4.

Notably, in the United States, glioblastoma is twice as common in white individuals compared to African Americans4.

Interestingly, some studies suggest that people with asthma or allergies may have a lower risk of developing GBM11.

Unlike other cancers, there is no specific screening for glioblastoma, and symptoms usually appear at an advanced stage.

How Is It Diagnosed?

The diagnostic process often begins with a general practitioner who refers the patient to a neurologist, neurosurgeon, or neuro-oncologist.

The assessment includes:

• A complete neurological exam (muscle tests, balance and coordination checks, sensory evaluations, reflexes, vision, hearing, language, reading, writing, drawing, memory, and comprehension tests)6.

• Medical imaging (MRI, CT scan)

• Blood tests

• A biopsy or surgical excision (meaning that the surgeon removes a portion of the suspicious brain tissue) is required for histopathological analysis. This is the only definitive method for confirming the diagnosis and determining the tumor’s type, grade, and level of aggressiveness.

An Aggressive and Invasive Tumor

Glioblastoma is characterized by its invasive and fast-growing nature. It belongs to grade IV gliomas, the highest malignancy level. Initially called “multiforme,” GBM is heterogeneous, making treatment particularly complex12;13. It often develops within three months in its “primary” or “de novo” form, without passing through a less severe tumor stage, affecting people over 60. The “secondary” form affects younger patients and progresses more slowly, as it originates from a low-grade glioma6;9 and so has a better prognosis.

Recurrence is almost inevitable, occurring in 75% to 90% of cases, typically within 2 to 3 cm of the initial resection margins.

Glioblastoma carries a poor prognosis. In France, the five-year net survival rate is only 7%, and most patients die within 14 months of diagnosis.

Most glioblastomas are supratentorial, meaning they lie above the tentorium, the structure separating the hemispheres of the cerebellum.

Distribution of glioblastomas in the left central hemisphere

Source : Des Étoiles dans la Mer – Vaincre le Glioblastome. (n.d.). Comprendre mon glioblastome [Brochure PDF]. & THERYQ

Current Treatments and Their Limited Outcomes

For the past two decades, the standard treatment for glioblastoma has relied on a combined approach:

- Surgical resection as complete as possible

- Radiotherapy (typically 60 Gy over six weeks)

- Chemotherapy with temozolomide (TMZ)14;15

This combination has led to a modest improvement in survival rates: median survival increased from 12.1 to 14.6 months with the addition of TMZ, and the 5-year survival rate reached 9.8%, compared to 1.9% with radiotherapy alone16;17. In 2015, the addition of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) low-intensity electric fields applied during maintenance therapy—further extended overall survival to 20.9 months and progression-free survival to 6.7 months18.

Unfortunately, these improvements remain limited, and no curative treatment exists to date. When recurrence occurs, which is an almost inevitable outcome, treatment options are scarce:

- Chemotherapies (e.g., lomustine, bevacizumab, regorafenib)

- Repeat surgery (rarely feasible)

- Experimental treatments available through clinical trials

For many patients, clinical trials represent a glimmer of hope. By being informed about ongoing studies, some may access innovative therapies still under evaluation, while also contributing to the advancement of scientific knowledge about this devastating disease19.

Living With Glioblastoma

The announcement of a brain cancer diagnosis is a profound shock for both patients and their loved ones. Symptoms that once seemed trivial suddenly reveal a far more serious reality, causing a brutal emotional upheaval. In this ordeal, being surrounded, supported, and listened to is essential. Being able to express fears and find comfort and hope through close and trusted relationships is fundamental.

Psychological support can offer a safe space for open expression and a compassionate, external perspective throughout this deeply personal battle. Peer support also plays a valuable role: sharing one’s experience and listening to others can be a powerful source of strength and resilience. Moreover, writing, participating in support groups, or getting involved in patient advocacy organizations are just some ways to make patients feel empowered and less alone in their journey.

The announcement of the diagnosis marks the beginning of a tumultuous period, combining uncertainty and hope. Between medical consultations, tests, and treatments, this journey—full of emotional highs and lows—often transforms one’s outlook on life. It prompts deep reflection on the meaning of existence, personal values, and one’s relationship to life itself.

Initial emotions such as fear, anger, and confusion may gradually give way to acceptance, resilience, and sometimes even a sense of inner peace. As challenging as it may be, this journey leaves a lasting mark on both patients and their loved ones, profoundly transforming them.

THERYQ’s Ambitions

At THERYQ, our ambition is to ultimately provide a solution for the treatment of glioblastoma using a combination of FLASH and Very High-Energy Electron (VHEE) technology. This mission is our driving force: providing hope for cancer patients that cannot currently be treated using conventional methods.

To achieve this, we are currently working on innovative projects that harness the potential of the FLASH effect. This technique consists of delivering ionizing radiation to cancerous cells in a fraction of a second at an ultra-high dose rate. This modality carrys promise of eventually enabling effective, shorter treatments with significantly reduced side effects compared to conventional radiotherapy24.

Other Treatment Options

Current research is increasingly focused on gaining a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind glioblastoma. This type of tumor generally does not rely on a single genetic abnormality, which is why targeted therapies alone often show limited effectiveness. As a result, the future of treatment is likely to depend on several emerging strategies:

- Combined therapeutic approaches11;13

- Harnessing the body’s immune system to fight the tumor, such as combining oncolytic viruses with immune checkpoint inhibitors to enhance anti-tumor immune responses20

- Incorporating advanced technologies such as next-generation sequencing and genome editing tools like CRISPR to better tailor treatments to each patient21

- In spring 2024, researchers in Florida also announced the development of a vaccine, which has received approval to begin trials in four human patients22;23

These innovative avenues offer new hope for improving outcomes in a disease where progress has long been limited.

Conclusion

Although rare, glioblastoma is a major medical challenge. Its aggressive nature, poor prognosis, and resistance to treatment make it a priority in oncological research. While recent decades have brought some progress, much remains to be done to improve patient survival and quality of life. Meanwhile, early and coordinated management by specialists, along with careful attention to initial symptoms, remain our best tools against this dreaded tumor.

Sources :

- Hartmann Oncology Radiotherapy Group. (n.d.). Glioblastome : Diagnostic, traitements et espérance de vie.

- Pouyan, A., Ghorbanlo, M., Eslami, M., et al. (2025). Glioblastoma multiforme: Overview of pathogenesis, major signaling pathways, and therapeutic strategies. Molecular Cancer, 24, 58.

- Interdisciplinary Oncology Centers. (n.d.). Glioblastoma.

- Stars in the Sea. (2024). Glioblastoma.

- Darlix, A., Zouaoui, S., Rigau, V., Bessaoud, F., Figarella-Branger, D., Bauchet, L., & Mathieu-Daudé, H. (2017). Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: A population-based national study. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 131(3), 525–546.

- Santé Magazine. (2023, January 25). Glioblastoma: Everything you need to know about this high-grade brain tumor.

- Hanif, F., Muzaffar, K., Perveen, K., Malhi, S. M., & Simjee, S. U. (2017). Glioblastoma multiforme: A review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 18(1), 3–9.

- Faleh, T. A., & Juweid, M. (2017). Epidemiology and evolution of glioblastoma. In Glioblastoma (pp. 143–153). Exon Publications.

- Reardon, D. A. (2012). Treatment of elderly patients with glioblastoma. The Lancet Oncology, 13(7), 656–657.

- (2021, April 1). Treatment of stage 4 glioblastoma – The role of radiotherapy.

- Zong, H., Parada, L. F., & Baker, S. J. (2015). Cell of origin for malignant gliomas and its implication in therapeutic development. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(5), a020610.

- CNRS Biology. (2023, August 28). Glioblastomas.

- Rajesh, Y., Sarkar, S., Banerjee, S., Paul, S., Dey, G., Majumder, M., & Mukhopadhyay, A. (2017). Insights into molecular therapy of glioma. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 38(5), 591–613.

- Stupp, R., Mason, W. P., van den Bent, M. J., Weller, M., Fisher, B., Taphoorn, M. J. B., … & Mirimanoff, R. O. (2005). Radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(10), 987–996.

- Stupp, R., Hegi, M. E., Mason, W. P., van den Bent, M. J., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Janzer, R. C., … & Mirimanoff, R. O. (2009). Five-year effects of radiochemotherapy on survival. The Lancet Oncology, 10(5), 459–466.

- Khaddour, K., Johanns, T. M., & Ansstas, G. (2020). The landscape of novel therapies for GBM. Pharmaceuticals, 13(11), 389.

- Tykocki, T., & Eltayeb, M. (2018). 10-year survival in glioblastoma. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 54, 7–13.

- info. (2025, January 23). Perspectives of artificial intelligence in the re-irradiation of adult glioblastomas.

- ÉCEVE. (2024, September 29). Surviving glioblastoma: My story about symptoms and hope.

- Glioblastoma Research Organization. (n.d.). Glioblastoma 101

- Gènéthique. (2024, April 22). “Shredding” cancer with CRISPR?

- (2025, March 4). Glioblastoma: Different treatments and life expectancy.

- Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute. (2024, April). Glioblastoma vaccine approved for first human trials.

- Schüler, E., Acharya, M., Montay‐Gruel, P., Loo, B. W., Vozenin, M., & Maxim, P. G. Ultra‐high dose rate electron beams and the FLASH effect: From preclinical evidence to a new radiotherapy paradigm. Medical Physics, 49(3), 2082–2095 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15442